Is there a Swiss form of colonialism?

Chocolate, banks, and mountains. Internationally, it is rare that a characterization of Switzerland comes absent these clichés. To eat Swiss chocolate, to bank with Swiss institutions, or to ski on Swiss mountains is to signify prestige. This reputation is not based solely on the quality of the chocolate, the banks, nor the mountains, but also on the very fact that they are Swiss.

However, while Switzerland and its industries benefit from the pretense that Switzerland was never a colonial power, many common “elements in Swiss everyday life, politics and scholarship“ are inflected by colonial relations.1 Cocoa does not grow in or near Switzerland. After colonial trade networks brought it to the country, Swiss marketers utilized racism in their advertising to separate their processed product from its origins and turn chocolate into a desirable commodity.2 The principal wealth of multiple Swiss banks came from investments in forced movement of enslaved people and trade across the Atlantic.3 The Swiss Alps only became “scientifically” embedded in the national character through encounters with other climates in the Dutch East Indies.4

1. Patricia Purtschert, Francesca Falk & Barbara Lüthi (2016) Switzerland and ‘Colonialism without Colonies’, Interventions, 18 (2): 289.

2. Purtschert, Patricia (2019). Swiss Chocolate and the Commodification of Black Bodies. In: Patricia Purtschert (Eds.), Coloniality and Gender in the 20th Century (122-131).

3. See for example Crain Merz, N. The transatlantic slave trade. Landesmuseum Zürich and Cooperaxion, Die Sklavengeschäfte der Finanzbranche

2. Purtschert, Patricia (2019). Swiss Chocolate and the Commodification of Black Bodies. In: Patricia Purtschert (Eds.), Coloniality and Gender in the 20th Century (122-131).

3. See for example Crain Merz, N. The transatlantic slave trade. Landesmuseum Zürich and Cooperaxion, Die Sklavengeschäfte der Finanzbranche

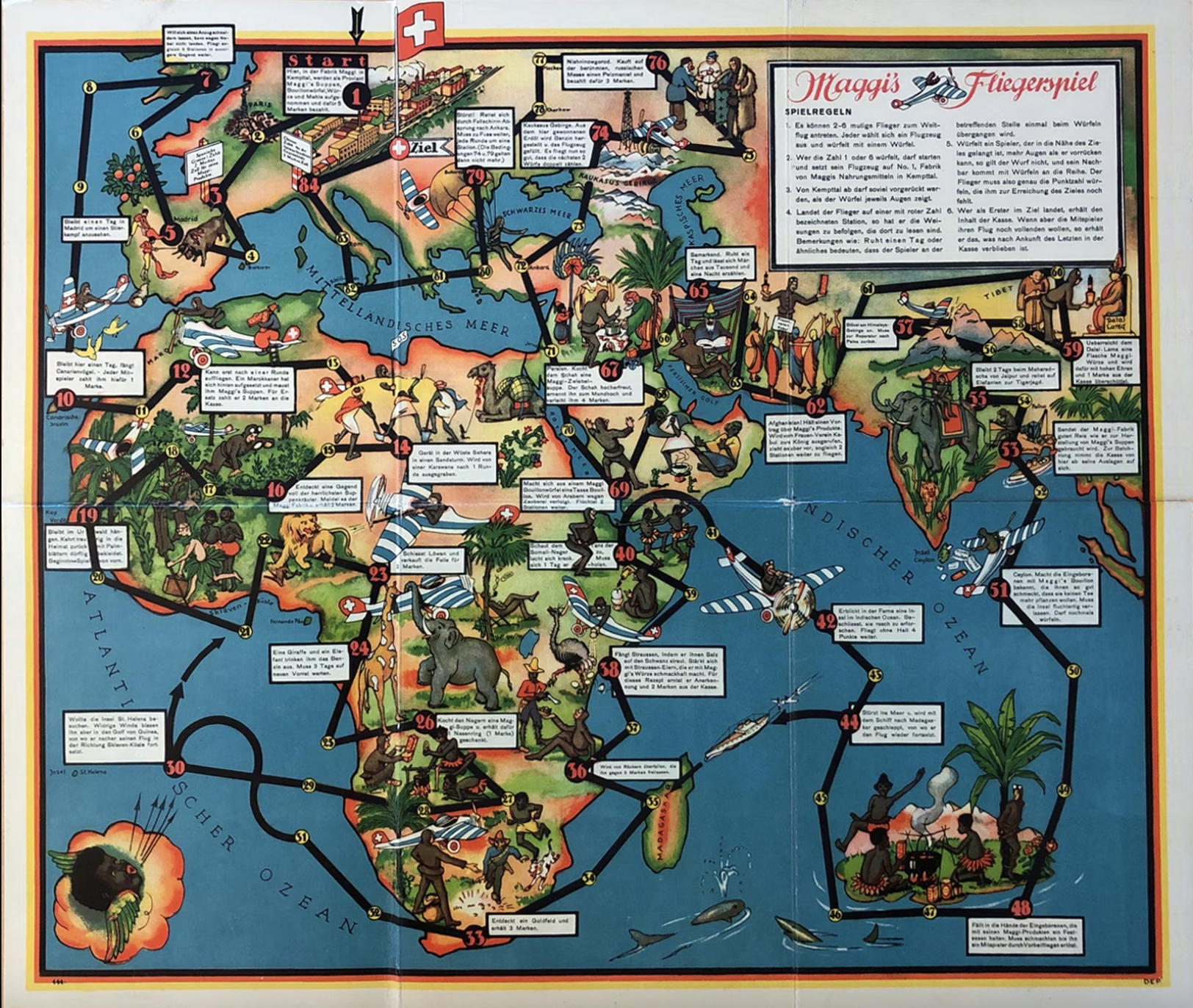

A 1930s “Fliegerspiel” board game issued by Maggi, now owned by Nestlé. Players travel through the African continent and West Asia by plane, taking off from Zurich. Each location of the territories, under Western imperialism, is depicted through racist illustrations, and described in terms of its contributions to Maggi’s supply chain. Image via Swissinfo.

4. Schär, B.C. (2015). On the Tropical Origins of the Alps. In: Purtschert, P., Fischer-Tiné, H. (eds) Colonial Switzerland. Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies Series. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

While other European countries violently scrambled to colonize the Global South, Switzerland capitalized on its position in the global hierarchies being put in place. It relied on colonial networks, not only for importing, exporting, and investing, but also for proselytizing and producing scientific knowledge.5 The Basel Mission, for example, was active in several countries of the Global South from 1815. Throughout this time, as the country’s entrepreneurs were building wealth and power through colonial exploitation, Swiss citizens had begun to “identify with the white subject of the European imperial space,” drawing “upon images of ‘blackness’ or ‘Africanness’ onto which the Swiss could project attributes they did not wish to be identified with.”6 By providing a foil against which a “self” could be rendered, colonialism contributed to both Swiss wealth and Swiss identity.

5. Schär, Bernhard C. (2015). Tropenliebe. Schweizer Naturforscher und niederländischer Imperialismus in Südostasien um 1900.

6. Michel, Noémi. (2015). “Sheepology: The Postcolonial Politics of Raceless Racism in

Switzerland.” Postcolonial Studies 18 (4): 414.

Within these top commodity groups, 48% of the materials extracted and sold on the entire planet can be traced to Switzerland’s corporations.

A tiny country with a footprint the size of the world

The ground for the tremendous success of Swiss companies today was prepared during Europe’s colonial era. Many of the racialized networks of power upon which companies built their wealth were not dismantled, even with the formal independence of many colonies. Rather, these networks have transformed to facilitate new forms of accumulation, extraction, and dispossession.

As of 2023, Swiss corporations play a disproportionately large role in global trade. Resource extraction typically takes place in low income countries, while profits are accumulated via corporate headquarters that are spatially, socially, and legally removed from the labor upon which the corporations rely.

Firms domiciled in Switzerland are responsible for trading 60% of the world’s metals, 60% of coffee, 50% of sugar, 35% of grains and 35% of crude oil.1 Because commodity trade can occur virtually, few of the goods ever physically pass through Switzerland.2 After extraction, raw materials are processed and packaged into consumer products in other countries along corporate supply chains. Low wage labor is recruited from many of the same racialized population groups who were once responsible for such work in colonized areas. The harmful environmental effects of industrial extraction and processing are also largely externalized to these same areas. This means some of the biggest companies on the planet can be “based” in Switzerland and benefit from low taxation, but have a very small material presence there.

Even with its limited corporate taxation, Switzerland benefits from hosting these large multinational corporations. They uphold the country’s reputation as possessing a strong, stable economy and innovative business environment. Corporations attract specialists to earn high wages at headquarters, regardless of working conditions in operations abroad. They secure Switzerland’s geopolitical position with its trade partners. Their shares are purchased to finance the pension funds on which Swiss retirees rely.3

Despite the documentation by Swiss and other researchers of this particular, corporate form of coloniality, regulatory restrictions to mitigate the negative social and environmental effects are lacking.4 Since the 1970s, multiple initiatives to hold Swiss corporations accountable for their actions in the Global South, such as the Koalition für Konzernverantwortung, have not yet achieved their aims.

As students learning and working in Switzerland, we find ourselves at the heart of these companies’ planetary operations. By researching their social and environmental effects, we hope to contribute to further insight and dialogue about the true footprint of Swiss corporations in the world.

1. Cited in Dobler, G., & Kesselring, R. (2019). Swiss extractivism: Switzerland's role in Zambia's copper sector. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 57(2), 225.

2. Dobler & Kesselring (2019), 228.

3. Theurillat, T., Corpataux, J., & Crevoisier, O. (2008). The Impact of Institutional Investors on Corporate Governance: A View of Swiss Pension Funds in a Changing Financial Environment. Competition & Change, 12(4), 307–327.

4. See for example the investigative work of Public Eye and Cooperaxion

Household products produced by Swiss companies are so ubiquitious they are hard to avoid. Which of these Nestlé-owned brands are you familiar with? Drag them into the nest to keep track.

Nestlé as a case study

Headquartered in Vevey, Switzerland, Nestlé consistently ranks as having one of the highest profits and market values in the world. Its products are sold in 186 countries, many of which host domestic and regional production facilities or supply raw commodities to be exported for processing.1 As of 2009, 3.4 million people in the developing world were earning their livelihoods somewhere along the Nestlé supply chain.2

The company began in 1867 as a small venture from pharmacist Henri Nestlé to sell his novel infant formula, made using cow’s milk and flour.3 Eight years later, he sold the company, and its new owners merged it with the enterprising Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company in 1905. Nestlé’s sales and production networks quickly expanded throughout Europe, then the Americas and the rest of the world, often through the acquisition of existing local brands.

Throughout Nestlé’s history, its successes in global market permeation came hand in hand with international corporate political activity. On the African continent, it aligned with European-appointed doctors to carry out colonial health policies meant to strengthen the available labor force.4 During WWII, it supplied millions of cases of Nescafé to the US military,5 while later benefitting from increased market access due to the political neutrality of the Swiss government.6 In recent years, its representatives influence public health policy in countries like the United States.7

While Nestlé is exceptional for its success and global market permeation, these same characteristics also make it representative of a broader reality in which corporations headquartered in Switzerland have outsized economic, political, and environmental effects on livelihoods and environments outside of the country.

1. Nestlé annual report

2. Creating Shared Value report 2009

3. Nestlé: Company History

4. Lola Wilhelm (2020) ‘One of the Most Urgent Problems to Solve’: Malnutrition, Trans-Imperial Nutrition Science, and Nestlé's Medical Pursuits in Late Colonial Africa, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 48:5, 914-933.

5. Nestlé: Comany History

6. Donzé, P. (2020). The Advantage of Being Swiss: Nestlé and Political Risk in Asia during the Early Cold War, 1945–1970. Business History Review, 94(2), 373-397.

7. Tanrikulu, H., Neri, D., Robertson, A. et al. (2020). Corporate political activity of the baby food industry: the example of Nestlé in the United States of America, Int Breastfeeding Journal, 15.

2. Creating Shared Value report 2009

3. Nestlé: Company History

4. Lola Wilhelm (2020) ‘One of the Most Urgent Problems to Solve’: Malnutrition, Trans-Imperial Nutrition Science, and Nestlé's Medical Pursuits in Late Colonial Africa, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 48:5, 914-933.

5. Nestlé: Comany History

6. Donzé, P. (2020). The Advantage of Being Swiss: Nestlé and Political Risk in Asia during the Early Cold War, 1945–1970. Business History Review, 94(2), 373-397.

7. Tanrikulu, H., Neri, D., Robertson, A. et al. (2020). Corporate political activity of the baby food industry: the example of Nestlé in the United States of America, Int Breastfeeding Journal, 15.

A non-exhaustive map of Nestlé’s global presence. Each grey dot represents one of its corporate offices or official facilities. Not pictured: many factories and processing sites, partner supplier farms, milk districts.

While it has dozens of offices and processing facilities around the world, Nestlé does not own most of the agricultural land on which the materials for its products are grown. This model has been part of the company’s success since its early days in Switzerland, when it developed its first “milk districts”-- semi-regulated areas where it encouraged independent dairy farmers to sell their milk and meet standards of quality and production.8 These milk districts are emblematic of Nestlé’s consistent efforts throughout its 150-year history to “develop” agriculture in the Global South. Presented as humanitarian initiatives, these types of training and education methods often deprecate local cultivation techniques in favor of those that are more valuable to a global capitalist system. In some countries, such as Zimbabwe, “guidelines” established during colonialism based on racist hygiene disinformation continue to favor white producers over farmers of color.9

A 1946 map of Nestlé’s presence on the African continent, including milk factories used for processing milk from surrounding milk districts.

Courtesy Nestlé Historical Archives Nestlé, Vevey. Copyright NESTLE S.A.

Nestlé training programs in the Global South, featured in its 1971 Annual Report.

Nestlé training programs in the Global South, featured in its 1971 Annual Report.Courtesy Nestlé Historical Archives Nestlé, Vevey.

Copyright NESTLE S.A.

The majority of commodities that are processed into Nestlé food products are bought from independent suppliers. The company has recently begun to divulge these actors along its supply chain, revealing tens of thousands of monoculture plantations growing sugar beets, oil palms, cocoa plants, and more.10 Some plantations are smaller co-ops who may supply Nestlé exclusively, while others are managed by massive third party distributors who sell to many food companies. The dizzying lists of thousands of suppliers highlights the difficulty of assigning legal culpability to the corporation, as in the court dismissal of child slavery allegations against Nestlé,11 or even accurately assessing its impacts on these areas in the form of environmental devastation, land redistribution, changes to social structure, and so on.

Activists with first-hand knowledge of the impacts of corporations on local communities have sounded the alarm bells, sometimes through the channels of NGOs. The Mỹky people of the Amazon have pushed back as Nestlé’s suppliers destroy their ancestral lands and livelihoods.12 In Papua New Guinea, Nestlé’s palm oil suppliers are held responsible for a complicated mix of environmental devastation, human rights abuses, and corruption.13 In Ontario, Six Nations activist Makaśa Looking Horse led efforts to stop Nestlé’s fee-free extraction of water from Indigenous communities, to which it then sold back its bottled products.14 While Nestlé has since sold its North American Water division, such practices continue as part of long-established patterns. In Vittel, France, citizens fight to reclaim the aquifer dried out by Nestlé’s bottling.15 In contrast to its sustainability messaging, Nestlé is considered one of the planet’s top causes of plastic pollution, creating deluges of waste largely exported and dumped in the Global South.16 In 2022, Filipino activists sent some of this dumped waste back to Nestlé asking the company to change its “destructive business model” and reduce its plastic waste.17

10. Nestlé website, 2019

11. See “Hershey, Nestlé, Cargill win dismissal in U.S. of child slavery lawsuit” (2022) in Reuters

12. See “‘This land belonged to us’: Nestlé supply chain linked to disputed Indigenous territory” (2022) in The Guardian

13. See Global Witness’s work on “The true price of palm oil”

14. See “This Indigenous Activist Is Taking a Stand for Clean Water Access in Canada“ (2021) via Global Citizen

15. See “Water conflict: Nestlé Waters in Vittel, France“ (2023) via the Atlas of Environmental Justice

16. See Talking Trash’s case study on Nestlé

17. See “Activists send plastic waste back to Nestlé, call out company for greenwashing“ (2022) via Greenpeace

11. See “Hershey, Nestlé, Cargill win dismissal in U.S. of child slavery lawsuit” (2022) in Reuters

12. See “‘This land belonged to us’: Nestlé supply chain linked to disputed Indigenous territory” (2022) in The Guardian

13. See Global Witness’s work on “The true price of palm oil”

14. See “This Indigenous Activist Is Taking a Stand for Clean Water Access in Canada“ (2021) via Global Citizen

15. See “Water conflict: Nestlé Waters in Vittel, France“ (2023) via the Atlas of Environmental Justice

16. See Talking Trash’s case study on Nestlé

17. See “Activists send plastic waste back to Nestlé, call out company for greenwashing“ (2022) via Greenpeace

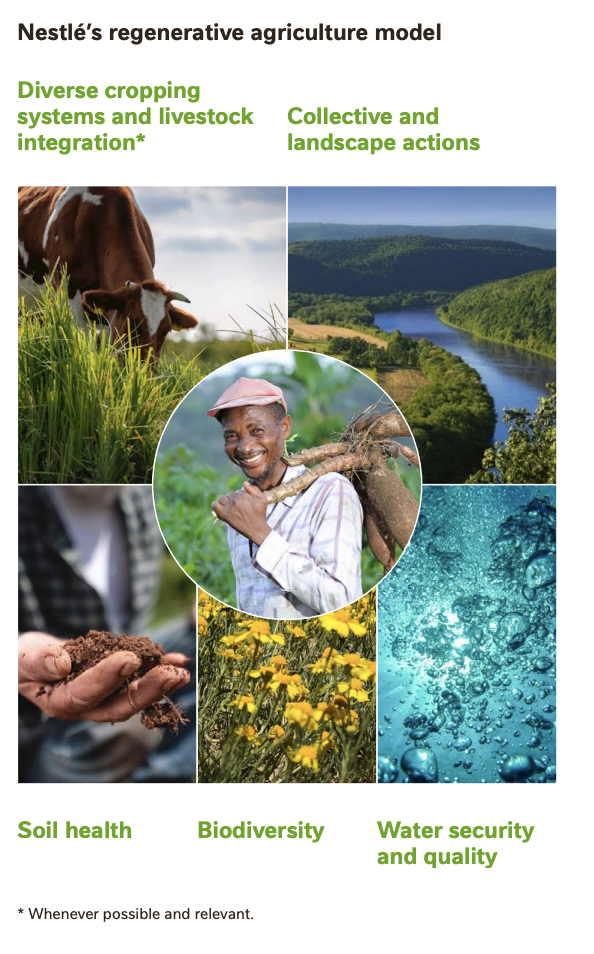

Regenerative agricultural model, to be used “whenever possible and relevant,” proposed during continued environmental and human rights abuses.

Via Nestle’s 2022 Creating Shared Value report

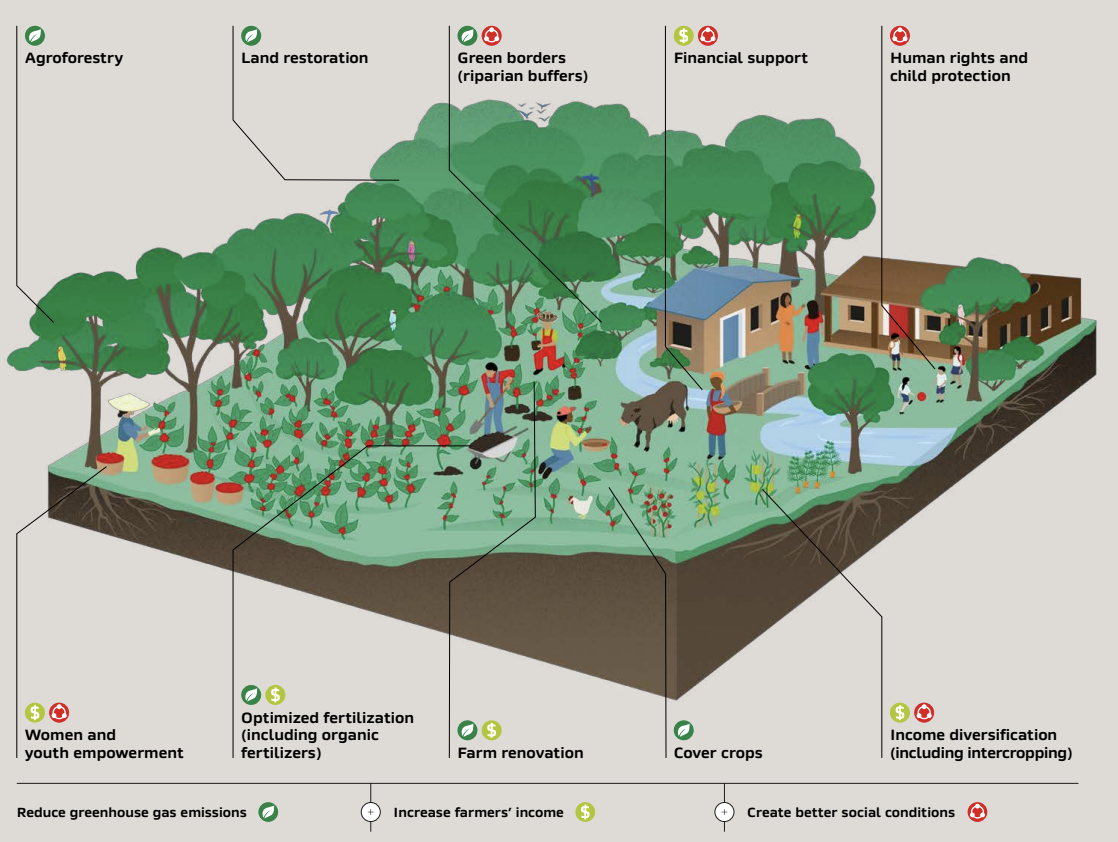

Proposed Nescafé model for 2030, focusing on land restoration rather than reparation.

Via Nestlé’s 2022 Creating Shared Value report

Nestlé’s selective development projects featured in its 2000 Management Report.

Courtesy Nestlé Historical Archives Nestlé, Vevey. Copyright NESTLE S.A.

Rather than engaging directly with these demands from the ground, Nestlé is accountable to its own set of metrics established in documents such as it Rural Development Framework and its “Creating Shared Value” plans. These initiatives have roots in early “corporate social responsibility” from the previous century and now exist as entire departments responsible for reporting the upholding of commitments to judicious consumers, largely in the West. Nestlé attempts to hinge its commitments around the perceived neutrality of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, which were set in 2015 and have been critiqued as “aligned with the financial interests of the business” due to corporate lobbying.18

Despite its selective interest in educational programs, at times focused on the theme of environmental sustainability, Nestlé has stated that it is not the role of business to provide public services. It instead argues that its corporate responsibility programs exist to maintain a community’s preexisting environmental conditions. It is difficult to determine how far down its value chain these claims extend, as the company has emphasized the autonomy of its suppliers to question its culpability. Adding to this paradoxical messaging, its public corporate social responsibility reports demonstrate a willingness, or even a sense of obligation, on part of the corporation to participate in aspects of development and sustainability transitions.

18. Archer, M. (2020). Appreciation. In C. Howe & A. Pandian (Eds.), Anthropocene Unseen: A Lexicon (pp. 47–51). Punctum Books.