Wheat - A Success Story for Whom?

Authors: Amanda Haas Halim | Clara Louise Alder Juul | Marie-Jean Malek | Runzhu Qian

“Wheat can be described as a modern success story in terms of its globalized production and consumption. But who benefits most from the spread of wheat?”

This project maps the trajectory of wheat from a single grain to flour in a Nestlé product, such as KitKat, Smarties, or morning cereals. This trajectory is entangled in a transnational network shaped by colonial legacies. Mapping thus makes visible the ways in which corporate and state actors shape landscapes of cultivation, production and consumption across geographies.

Nestlé’s own narrative depicts corporations as responsible actors and stakeholders in securing worldwide food safety. Our project questions this narrative by shedding light on unequal and complex power relationships of those involved and affected. A narrative that goes beyond the corporate record can incorporate stories from cities and countrysides, connecting them in a transnational network.

“At Nestle our aim is to help leave the world better than we found it, and as the world’s largest food and beverage company, we have a tremendous opportunity to help create a regenerative, healthy food system while also working with the local farming communities that employ it.” (World-Grain, July 2023)

After the Second World War, wheat was one of the most hopeful contenders in the fight against world hunger. Using their ‘Miracle Mexican Wheats’, Norman Borlaug and his colleagues saved millions from starvation by developing and planting wheat varieties that resist diseases and insects. It was essential for a secure food supply, human health, and reducing the use of chemical controls.

The stakes were high: the newly founded World Food Programme described wheat as a staple food that, if its production could be expanded and accelerated, could alleviate most of the world's hunger. Food security and food safety have become terms used to describe such future visions.

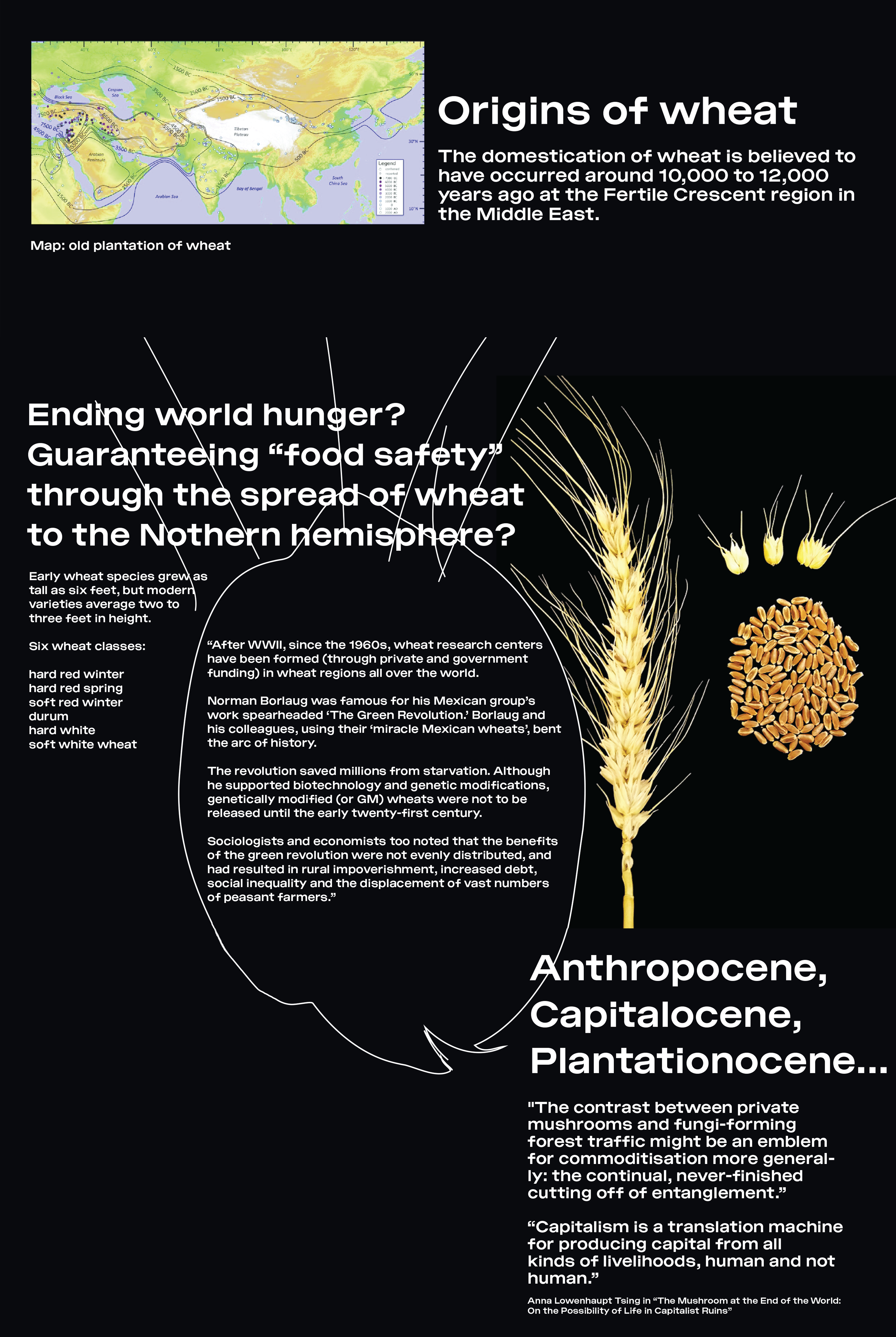

As wheat production has shifted from its original warmer-climate roots in the Middle East to the northern hemisphere, six modern wheat varieties have emerged, undergoing genetic modification, height adjustment, and adaptation to resist pests and fungi, withstand colder climates and fertilize. This transformation made its production not only more efficient but also far more lucrative. However, sociologists and economists noted that the benefits of this so-called “Green Revolution” were not evenly distributed, and were contradicted by rural impoverishment, increased debt, social inequality, and the displacement of vast numbers of peasant farmers.

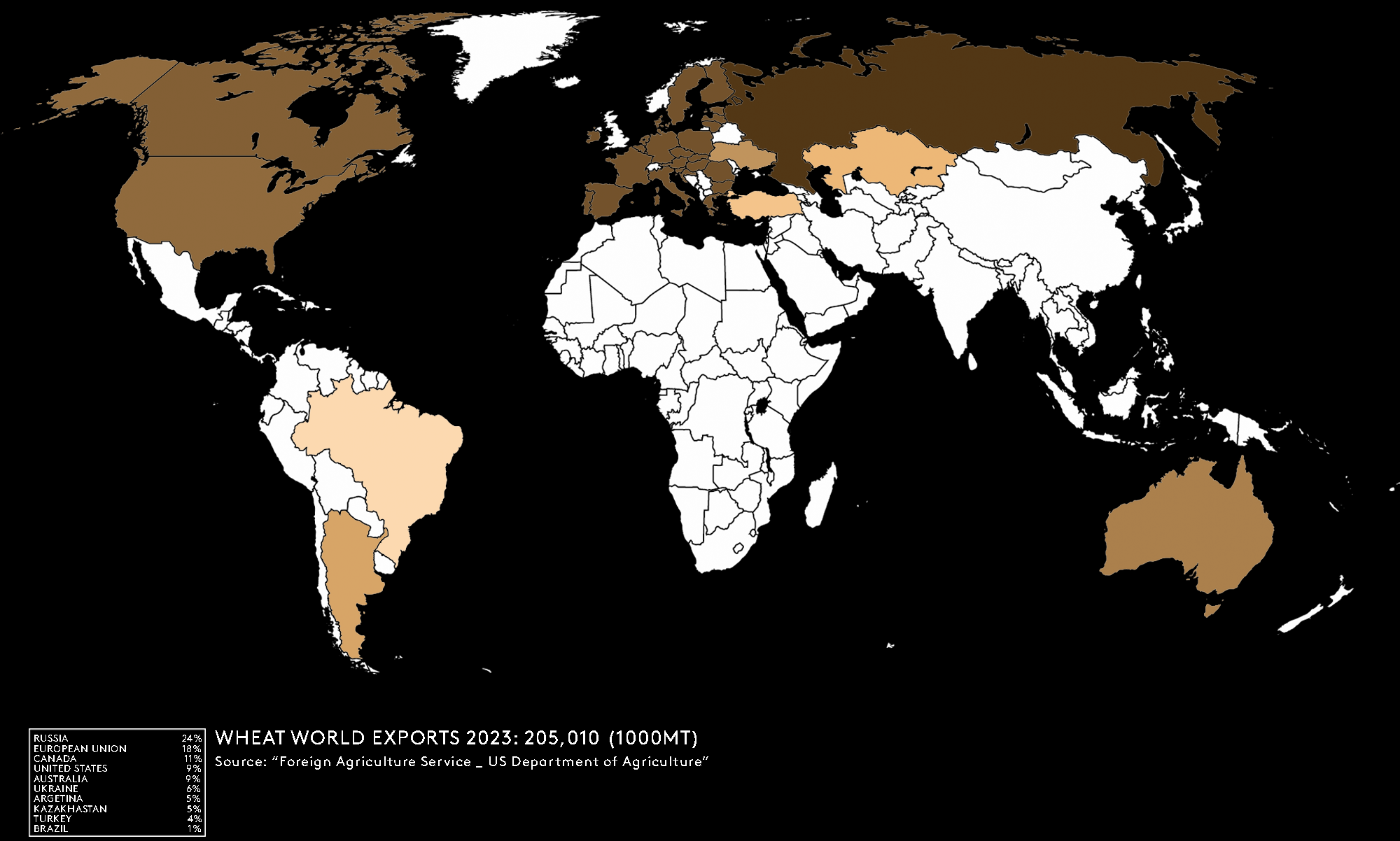

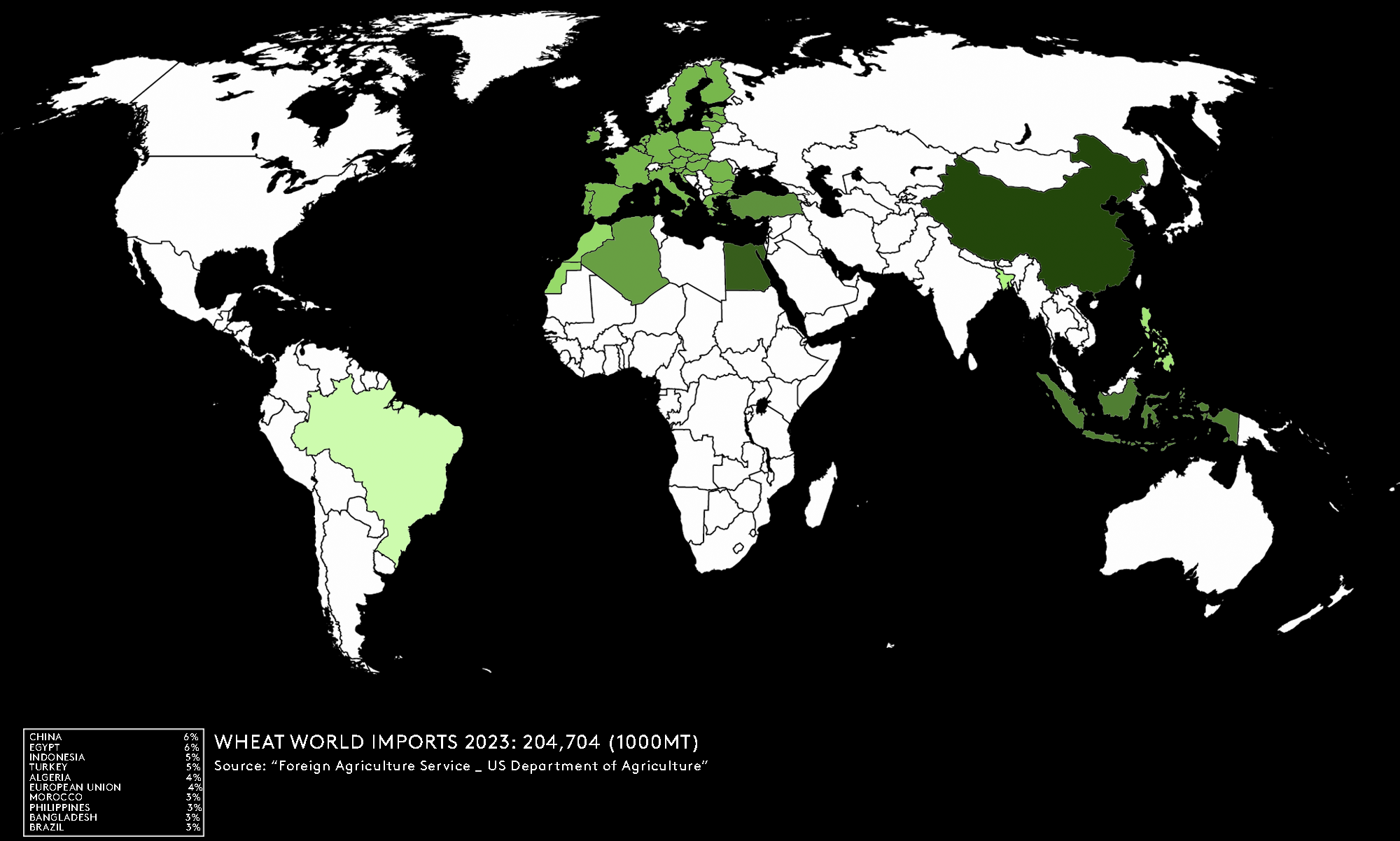

By analyzing the global food supply chain of wheat, from cultivation to consumption, we could identify geopolitical power dynamics. Tracing who controls the production, circulation, and pricing of wheat on a global scale provides insight into the ways in which food systems can sustain or disrupt political relationships. In "The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins," anthropologist Anna Tsing writes that ‘urbanization is multi-scalar connecting various places and territories and has a tremendous impact on our perception of and being in the world’ (p. 49).

Understanding cities from an ecological perspective stresses the need to consider the urban as a territorial formation with links to many other places. It shows how the production and trade of wheat becomes a mediator of urbanization processes as well as their materialization.

In order to grasp the operational landscapes of wheat and the influence of the global food network on our daily lives, we extended our investigation beyond the corporate record. The transformation of wheat production then emerges as a planetary issue.

We focused on two constituents that are differentially entangled: Ukrainian local farmers and Egyptian consumers. Interconnecting narratives from their lifeworlds substantiates this entanglement begins to suggest a counter-narrative to the one advocated by Nestlé and its “grain giant” suppliers such as ABCD (standing for Archer-Daniels-Midland Company, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus).